When Anton Molina talks about modular science, he doesn’t just mean smaller experiments or cleaner code. For Anton, modularity is a way of doing science that breaks research into self-contained, reusable pieces—protocols, data, and designs that can be independently validated, remixed, and combined. It is a method designed to make research faster to share, easier to replicate, and simpler to build upon.

As Director of Open Source Ecosystem at b.next, Anton leads the development of the company’s open source tools, practices, and community, collectively called Nucleus. As the core development team and stewards of Nucleus, b.next plays a unique role: providing the means to coordinate the synthetic cell research community through a grass-roots approach rooted in open collaboration, not competition.

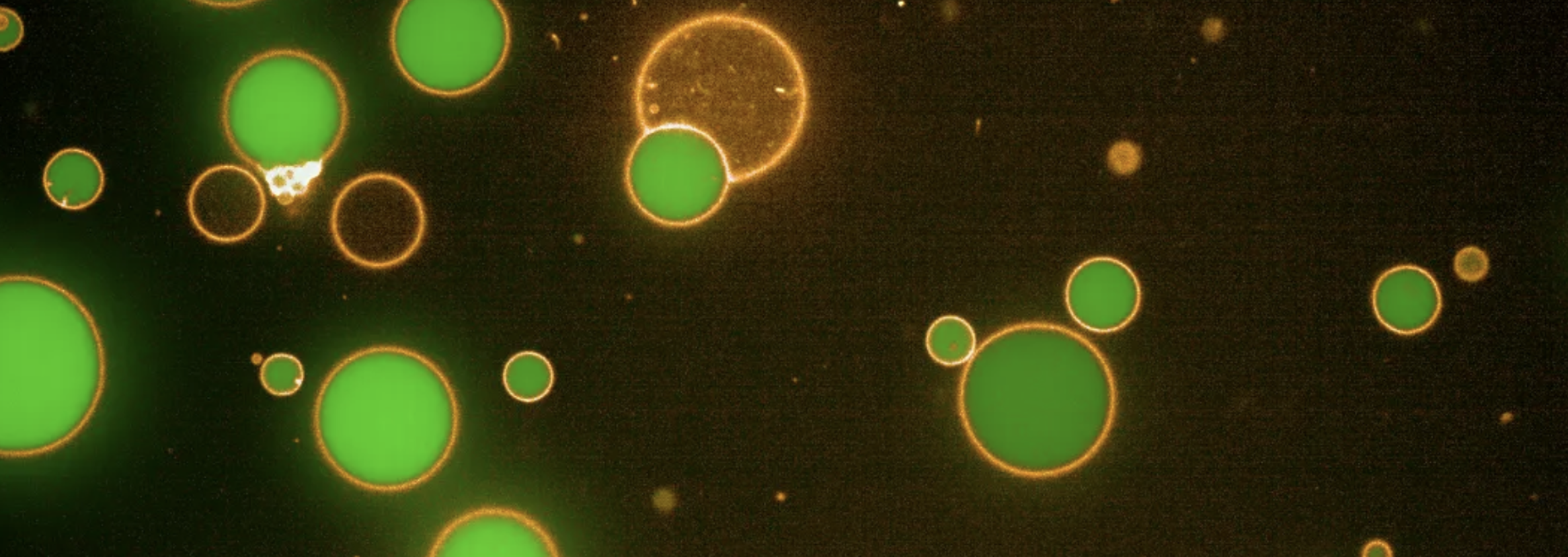

Together, they aim to build synthetic cells: non-living, genetically programmed biomolecular machines constructed from the bottom up using known components. Each synthetic cell is made from biochemical modules—energy regeneration, sensing, actuation and logic, which are the primary focus of their modular science efforts.

Anton points to an early success story:

Our first workshop helped a group of summer students get started making synthetic cells. In our parlance, they implemented a membrane and reporter module. Normally, the students would have to cobble together a protocol from existing literature, troubleshooting might take the whole summer—we were able to get students proficient within two days.

Anton Molina, PhD

Building the Infrastructure for Sharing¶

A key component of the Nucleus infrastructure is Developer Notes (DevNotes), which gives researchers a place to publish biochemical modules as self-contained “data packets,” complete with the data, designs, and analysis needed to implement them. DevNotes are based on Jupyter Notebooks, allowing us to integrate tools from open-source scientific computing and software development communities. The result is the ability to work more efficiently and provide greater visibility into the parts of the research workflow that are often not shared with existing publication practices, such as experimental design and analysis.

This is more than a convenience. It is a fundamental rethinking of how science communicates and collaborates. The approach draws inspiration from the Request for Comment (RFC) series created by the Internet Engineering Task Force in 1969, which encouraged timely sharing over polish and created a living record of more than 9,000 documents that underpin the internet we use today.

DevNotes aim to do the same for the synthetic cell community: lowering the barriers to participation, encouraging iteration, and giving credit, through DOIs, for contributions that might never appear in a traditional journal article. The goal is to enable researchers to share useful information in days and weeks rather than the months and years involved with typical journal timelines.

Coordination at the Field Level¶

Traditional research has focused on modifying existing organisms with researchers often working in isolation, struggling to build on the work of others. b.next is taking a different path, building cells from scratch—designed for engineering, reuse and for collaboration.

Nucleus, the open-source ecosystem developed by b.next, provides the shared foundation to make this possible. It is not an “operating system” in the computing sense, but a set of shared resources that work together: protocols, DNA designs, validated tools, and documentation.

b.next hosts regular synthetic cell developer meetings, maintains a collection of validated protocols and plasmids, and organizes workshops that introduce researchers to Nucleus tools and open science workflows. Our goal with all of this is to get researchers to think about how their work either builds on or supports the work of others in the field. By emphasizing interoperability and reuse, Nucleus makes it far more likely that someone else might pick up where they left off.

Anton Molina, PhD

Molina believes that innovating on communication is in many ways as important as the technical innovation Nucleus otherwise supports. Communication, especially written communication is key for Nucleus to serve as a coordination solution for the research community. By reducing the scope of publication into smaller contributions, Nucleus also makes it easier to replicate experiments. This shifts quality control from peer review to peer replication, rewarding researchers not just for discovery but for validation.

The Power of Modular Workflows¶

Scientists often face a tradeoff: keep pushing forward with the next experiment or pause to document, share, and curate their work.

“More often than not, the scientist is gonna say ‘more science!’, not curation or documenting,” Anton says with a grin.

The barrier is not just time. Scientists are expected to package their work into a complete narrative before it is considered worth publishing. Because careers hinge on a handful of high-impact publications, researchers can spend months perfecting a manuscript before sharing.

Nucleus and its DevNotes flip the equation. By encouraging research to be packaged into small, shareable modules, scientists can publish and progressively build credit in parallel.

“A module is like a little gift that I can share,” Anton says. “A project often feels unwieldy. A module is manageable. It’s something I can handle.”

Licensing as Infrastructure¶

One of the most transformative aspects of Nucleus is its open-source licensing approach. It provides a clear and permissive path for both academics and industry, including startups and large enterprises, to use, build on, and deploy these tools with confidence. This strengthens the legal foundation for academic sharing and broadens participation, making it easier for the entire ecosystem to benefit from and contribute to the work.

Without this clarity, researchers and companies could face a patchwork of institutional agreements before legally deploying these technologies. Nucleus removes that barrier with a single, transparent license that enables adoption and extension at scale.

Beyond Technical Success¶

Technical success alone is not enough. Anton warns that progress will still stall if communication stays locked in papers and conferences.

“If we were to succeed with the technical aspects of the Nucleus distribution without also thinking about how we communicate, it would be like having access to an incredibly powerful computer but still relying on horse and carriage to talk to one another—it’s unlikely we could have continued pushing the boundaries of computers without also having the internet,” he says. “Even the best technical tools won’t accelerate progress if we are still limited by outdated modes of communication.”

Modular publishing tackles that problem directly by making research outputs replicable, interactive, and citable. The goal is a living scientific record that moves as quickly as the science itself.

The Human Element¶

Anton’s own journey mirrors the openness he champions. Raised in the Bay Area, he describes feeling like an outsider in the heart of Silicon Valley—a region that, for all its technological promise, feels closed to those outside the tightly-knit inner circles.

“Transparency and no barrier to participation are the key premises of open source. You shouldn’t have to ask permission to take part.”

That ethos has guided him from building frugal scientific hardware during his PhD at Stanford, to coordinating distributed manufacturing during the COVID-19 pandemic, to leading open source and open science practices for engineering biology at b.next.

Looking Ahead¶

As b.next launches new components of Nucleus, including DevNotes and Nucleus Hub, Anton sees his role as laying the rails for others to do great science.

Although Nucleus is currently focused on the bottom-up synthetic cell community, the lessons being learned about modular workflows, open licensing, and new approaches to publishing apply far beyond synthetic biology.

We’re so familiar with seeing science presented at the scale of five polished figures, it can be difficult to imagine that different ways of working are possible. Anton offers that starting can be simple: “Start by finding the right scope. A module should feel like something you can deliver comfortably. Then build the container around it so it’s easy to share.”