The tools of science have changed, the way we share science has not¶

Modern research is collaborative, computational, and built iteratively — from large datasets to carefully developed protocols, pipelines and research software. And yet, the systems we use to share that research remain largely unchanged.

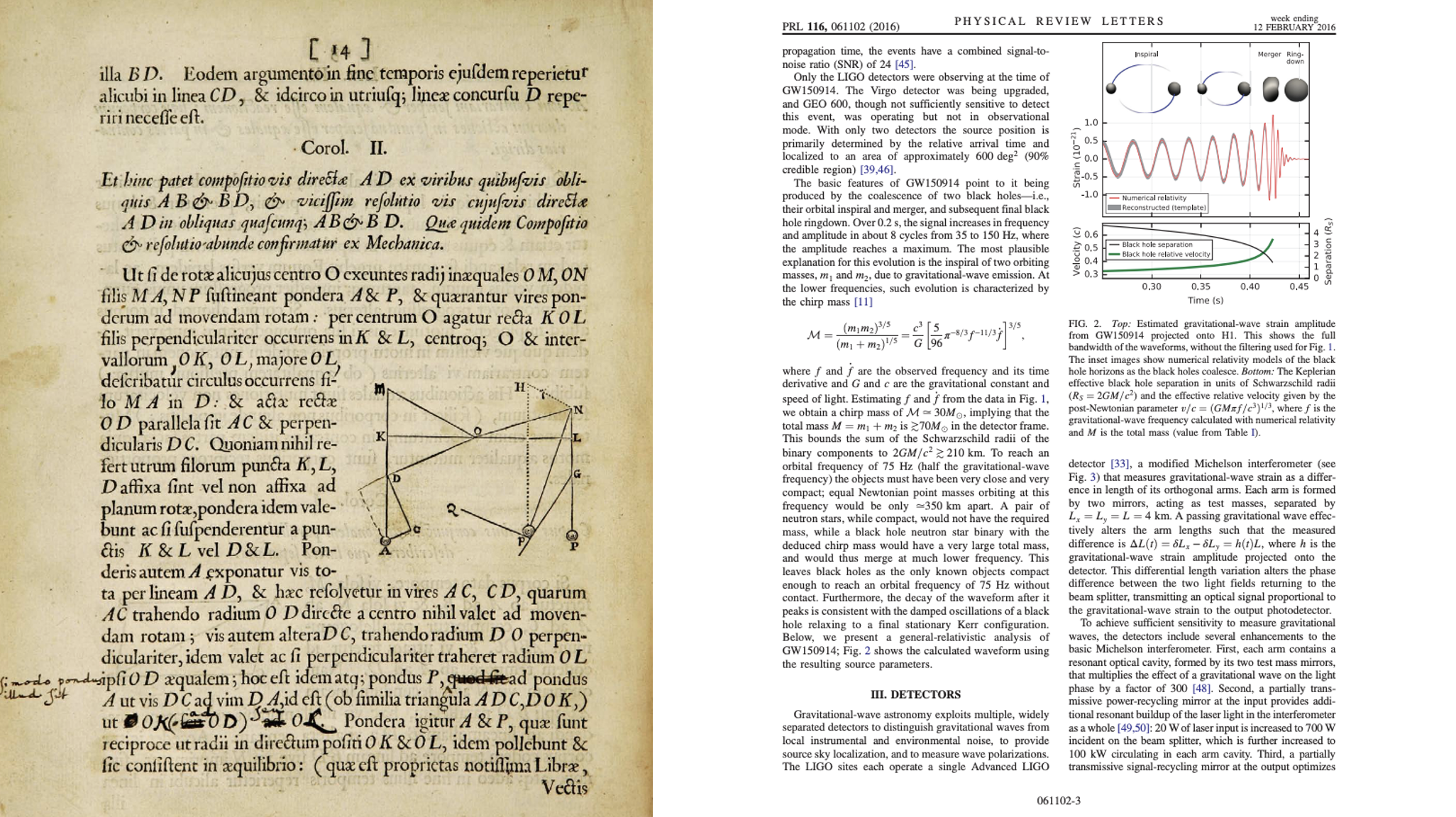

From Newton’s Principia to LIGO’s Nobel-winning paper on gravitational waves 350 years later, the format of scientific communication has barely evolved Figure 1. Too often, tables are still shared as images; links to data, methods, and results are missing; software is sidelined; “data available upon request” is still too common a refrain. Opportunities for reuse, reproducibility, collaboration, and incremental insights are lost.

Figure 1:A snapshot of scientific progress — and the constraints on our communication. On the left, a page from Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687) filled with geometric diagrams and dense Latin prose. On the right, a 2016 Physical Review Letters article describing the Nobel-winning detection of gravitational waves, featuring modern typesetting, equations, and plots. Despite the scientific advances between these works, both represent ideas in static formats — disconnected from the data, methods, or computational steps that underpin them.

Over the past two decades, there have been major shifts in when scientific results are shared and who has access to them. The open access movement — alongside the rise of preprint servers — has pushed scholarly communication toward greater access and earlier dissemination. These changes have expanded participation, accelerated feedback, and removed barriers to the scientific record.

Access alone is not enough¶

Open access to the scientific record is critical — and we must continue to build that foundation collectively. However, access alone does not bridge the disconnect between how science is conducted and how it is communicated.

Too often, the tools, incentives, and economic models that shape scientific communication are built around the moment of sharing — not the ongoing, iterative work that comes before, or the critical reuse that comes after.

Science needs mindsets driving our infrastructure that support the full arc of research — from early exploration to validation to discovery to eventual reuse — and the full breadth of what science includes: data, software, methods, protocols, and of course narrative stories. Science deserves communication practices that reflect the true nature of modern science: iterative, integrated, collaborative, and continuous.

Iterative, integrated, collaborative, continuous¶

Today, researchers are working at the edge of what’s possible — generating large-scale datasets, running complex simulations, developing reusable codebases and protocols, and collaborating across disciplines and borders. But when it comes time to share that work, we’re still forced to flatten it into static documents and disconnected, hidden supplements. The systems we rely on to bring it all together — journals and preprint servers — were not designed for how modern science is actually done.

Scientific communication today is fractured, slow, and constrained by the medium and mindset of print. Articles are published months or years after the work is complete. Core research artifacts — software, data, methods — are treated as secondary, if they’re included at all. And building on someone else’s work too often means starting from scratch — a new introduction, a novel story, new analysis code.

Science deserves better.

It deserves infrastructure that reflects what science truly is: iterative, computational, data-rich, and continuously evolving — supporting the ethos of standing on the shoulders of giants to easily reuse work and build upon ideas.

We believe in sharing early, often, and — when appropriate — openly. Prioritizing small, meaningful updates over large, infrequent ones. Changes towards continuous process — continuous science — allows feedback and review to happen when it matters — during the research process, not only after it’s done. It means that leading practices of reproducibility, attribution, transparency, and reuse are built into our tools and workflows, not left to researchers to retrofit at the point of publication.

Figure 2:Science is continuous — but our tools and systems are not. Continuous Science is a model of connected research and communication: a system where authoring, reviewing, publishing, and refining are integrated with collecting, analyzing, and sharing data. Research and communication are not separate cycles, but parts of a single, iterative loop — where automation supports quality, connection enables feedback, and ideas are networked to be easily built upon and reused.

Continuous science demands better integration. Today’s researchers move between dozens of disconnected systems — writing, coding, analyzing, illustrating, sharing — with little connective tissue. In a continuous model, the narrative is tightly woven with the code, the data, the protocols, and the reasoning and references behind them. You don’t just read about the simulation — you run it. You don’t just cite a paper — you reuse or reference the exact figure, equation, paragraph, or method.

We envision a world where lab groups can share when they are ready, and that sharing automatically supports the highest standards. Where publishing is not gatekept or oversimplified, but made possible through automation, validation, and thoughtful defaults. And where the tools for professional scientific communication are not designed and reserved for publishers, but placed directly in the hands of researchers.

Our ambitions for open, iterative, reproducible, collaborative, and continuous science are outpacing the systems we have to support them.

You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.

James Clear (Atomic Habits)

It’s time to build integrated systems that embrace the full spirit of open science — where collaboration, data sharing, and computational integration are built in, not bolted on. This is the vision and direction we are stewarding at Continuous Science Foundation — not alone, but alongside a growing number of researchers, developers, societies, companies, and institutions who are already pointing the way forward. The work ahead is to give this vision shape, coherence, and shared momentum.

Why we started Continuous Science Foundation¶

Continuous Science Foundation (CSF) was founded in 2024 by researchers, technologists, and communicators who saw a gap between how science is conducted and how it is shared. Operating as a 501(c)(3) non-profit under the fiscal sponsorship of Rapid Science, CSF is committed to be an aligning force between the doing of science and the communicating of science. We are not here to build a platform, offer a service, or build infrastructure — we believe in better connections to science in progress — to make it easier for researchers to continuously share their work in ways that are more useful, more interoperable, more reusable.

The year ahead¶

In 2025, we will host our first in-person gathering in Banff — a small, invitation-based event supported by The Navigation Fund. This gathering will bring together researchers, tool-builders, infrastructure providers, institutions, and community leaders to co-create a vision and a movement. Together the group will help define a roadmap for shared action across multiple organizations. This roadmap will help define areas for working groups to articulate shared standards and leading practices. To reinforce continuous practices and connected work we will contribute and maintain a library of open-source tools that aim at connections between data, code, and narrative and ways to publish and share science professionally. Over the coming year we will also form our governance structures to ensure our efforts at Continuous Science Foundation reflect the needs and priorities of the broader open science community.

The work of improving scientific communication is shared work. If you’re a researcher, contributor, developer, or open science advocate, we’d love to connect.

Copyright © 2025 Cockett et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creators.

- CSF

- Continuous Science Foundation