After mapping both the current and ideal states of scientific communication through the Iceberg exercise, we turned our attention to bridging the gap between the two. The next step was to imagine how we might actually get there.

This part of the workshop focused on idea generation—spanning the grounded and practical to the imaginative and aspirational. Building on the insights surfaced earlier in the day, participants revisited the areas they had prioritized for change: What structures or mindsets need to be reimagined? What habits or assumptions could we let go of? What new patterns could we intentionally design toward?

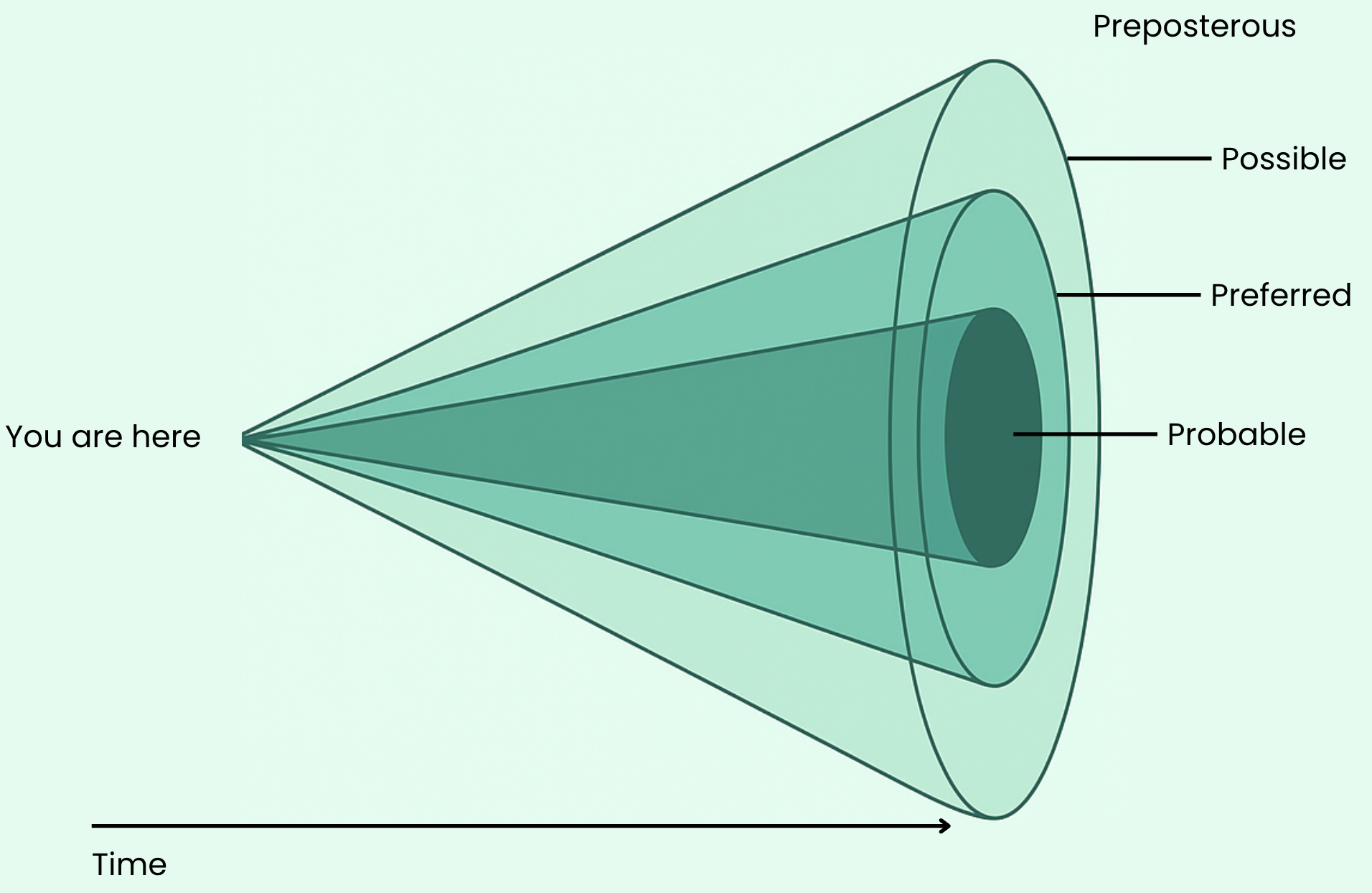

To guide this creative process, we introduced the Cone of Future Possibilities. This exercise is designed by Wildly Open to help organizations think strategically about the future. Rather than focusing solely on what’s most likely to happen, the Cone encourages teams to consider what is possible—and more importantly, what’s worth investing in. It is a tool for pushing beyond current constraints to surface bold, generative ideas that can shape the system, not just react to it.

With the day’s case studies, personas, tensions, and group reflections—and lunch—as fuel, participants began charting new directions—stretching their thinking toward the kinds of futures they not only imagine, but believe are possible to build.

Figure 1:Cone of Future Possibilities. This framework illustrates the range of futures we can imagine—from the probable (what’s likely to happen) to the preferred (what we want to happen), the possible (what could happen), and even the preposterous (what seems implausible today). It encourages moving beyond prediction toward intentional, aspirational design—shaping the future rather than simply reacting to it.

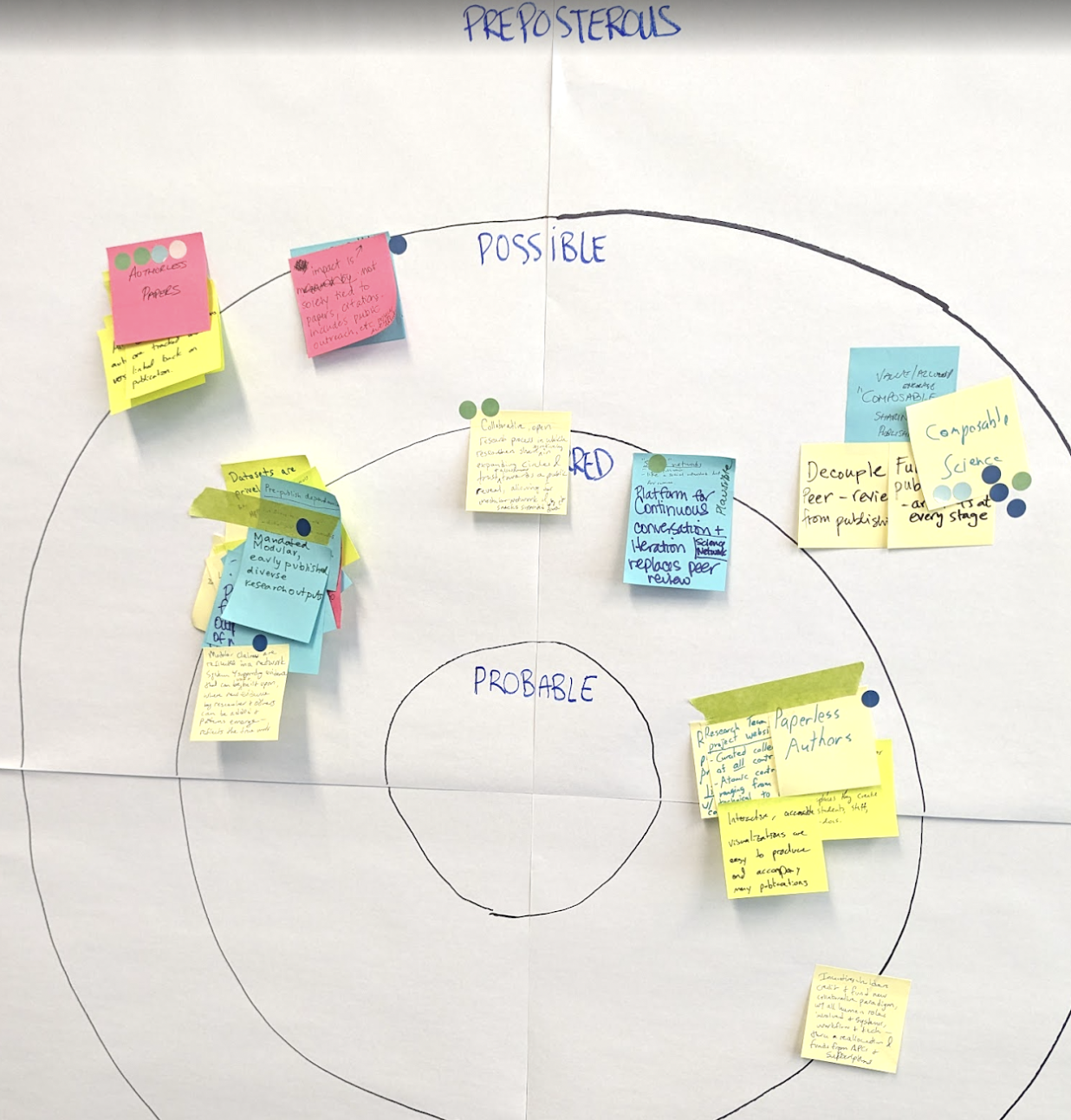

First, each person spent time generating individual ideas—tools, mindsets, cultural shifts—writing one idea per sticky note. In groups of three, they then clustered and refined their thinking, narrowing down to two promising concepts per group. Finally, these trios merged into larger table groups to select three final ideas to pitch back to the room — nine total ideas. These ideas were pitched to the room, then we voted during a coffee break. ☕️ 🗳️

Participants proposed a wide range of ideas to reshape how science is communicated, credited, and reused. These ideas spanned both practical improvements and visionary shifts—grounded in the belief that today’s systems can be restructured to better support openness, iteration, and collaboration. The strongest support went to Composable Science, the idea of breaking research into peer-reviewed components—figures, code, data—that can be reused and cited independently. This was complemented by calls for snackable, modular outputs, project-based websites, and continuous, conversational peer review, all designed to reflect the way science is actually done rather than how it’s currently published.

Other proposals focused on attribution and incentives: authorless papers and contribution graphs would replace traditional author lists with a richer, networked model of credit. New impact metrics would reward engagement, reuse, and diverse contributions—not just citations. Ideas like expanding circles of trust and claim networks introduced new ways to validate and evolve scientific knowledge collaboratively over time. Even though some suggestions—like fully reallocating funding streams—received less traction, the overall message was clear: by investing in modular systems, transparent practices, and infrastructure that reflects how science really works, we can build a more open, resilient, and equitable future.

Opportunities¶

- Modular, Early, Snackable Research Outputs (1 votes)¶

- Research should prioritize early, modular, diverse outputs like data, code, and figures before contextual narrative text. This “snackable” approach supports reuse and incentivizes sharing components. However, credibility and appropriate credit are essential to encourage participation.

- Rethinking Impact Measurement (1 vote)¶

- Impact metrics must move beyond article-centric, citation-based measures to include diverse contributions: public engagement, team roles, and global inclusivity. While challenging to implement, it’s seen as essential for recognizing broader scientific contributions.

- Continuous Conversation & Iteration (Replacing Peer Review, 1 vote)¶

- Traditional peer review is slow, competitive, and often toxic. A dynamic, iterative conversation model could allow researchers to revise and improve work with feedback from a broader, more inclusive network, rather than relying on siloed or adversarial reviews.

- Project-Based Research Websites (“paperless authors”, 1 vote)¶

- Funded research projects should maintain curated websites containing all outputs: data, code, visualizations, technical reports, and outreach materials. This promotes transparency, credit for diverse contributions, and iterative reuse of research components.

- Composable Science (6 votes)¶

- Deconstruct research papers into individual, peer-reviewed components (e.g., figures with code, datasets, methods), allowing others to reuse, remix, and build upon them. This supports collaborative authorship and challenges current notions of self-plagiarism.

- Authorless Papers / Contribution Graphs (4 votes)¶

- Shift away from author lists to a graph of contributors and artifacts, recognizing everyone’s role—from data curators to software engineers. This approach captures the full network of contributions to a piece of research.

- Collaborative, Iterative Research Sharing (Expanding Circles of Trust, 2 votes)¶

- Adopt a modular, claim-based research model where evidence supports claims, shared in expanding networks (from close collaborators to public). This enables iterative validation and reuse of research findings within evolving communities.

- Claims Network & Evidence-Based Science Evolution (1 vote)¶

- This modular claim-sharing results in a network system where claims are linked to evidence and can be expanded, reused, or built upon. The system reflects the real evolution of science as a collective, evidence-based process.

- Incentive Alignment & Funding Reallocation (0 votes)¶

- Transition current funding (e.g., journal subscription fees, APCs) to support collaborative, open, and iterative research systems. Incentive holders (funders, institutions) must recognize diverse contributions and invest in infrastructure that supports these new workflows.

Figure 2:Each person spent time generating individual ideas—tools, mindsets, cultural shifts—writing one idea per sticky note. In groups of three, they then clustered and refined their thinking, narrowing down to two promising concepts per group. Finally, these trios merged into larger table groups to select three final ideas to pitch back to the room — nine total ideas. These ideas were pitched to the room, then we voted during a coffee break. ☕️ 🗳️ Each participant had a single vote.

Workshop Outcome - Composable Science¶

We aligned at a high-level opportunity to focus our energy and movement around: “Composable Science”. We then went to the top of Sulphur Mountain to have dinner, go on a walk — and start to try the movement of composable science on for size.