On the first day of the workshop we set context, introduced each other, created personas, went through the pre-workshop survey results, used the iceberg model to go deep into the mindsets and systems behind events, ideated a preferable future and chose a movement together.

Case Studies as Touchstones¶

Before diving into the work of reimagining scientific communication, we grounded ourselves with two powerful case studies. These stories from seemingly unrelated fields—urban design and software development—offered clear, compelling examples of how system-wide change often starts from the margins and requires focused changes on systems or mindsets. By reflecting on curb cuts and continuous software development, we set the stage for imagining how similar principles could reshape the ways we share and build science.

In the 1970s and '80s, disability advocates fought for curb cuts—small ramps on sidewalks that allowed wheelchair users safe passage. Once implemented, these seemingly niche accommodations transformed public spaces for everyone: parents with strollers, delivery workers, travelers, and runners alike. The big idea is simple: when we design for the margins, we create systems that are more inclusive, resilient, and beneficial for all.

The transition from rigid waterfall methods to Agile and continuous software development reshaped how software is built. Inspired by lean manufacturing, developers introduced small, incremental changes, automated testing, and continuous integration, unlocking massive improvements in delivery speed, quality, and team collaboration. The key takeaway: change isn’t a disruption, it’s a constant to be designed for—by adopting iterative, continuous practices, we can accelerate progress while maintaining rigor and resilience.

These case studies served as touchstones throughout the workshop, reminding us that meaningful change often begins at the edges—with overlooked users, or outdated processes—and grows through intentional, iterative design. They helped frame our collective work: identifying the small, strategic shifts that could unlock a more inclusive, flexible, and future-ready system of scientific communication.

Personas¶

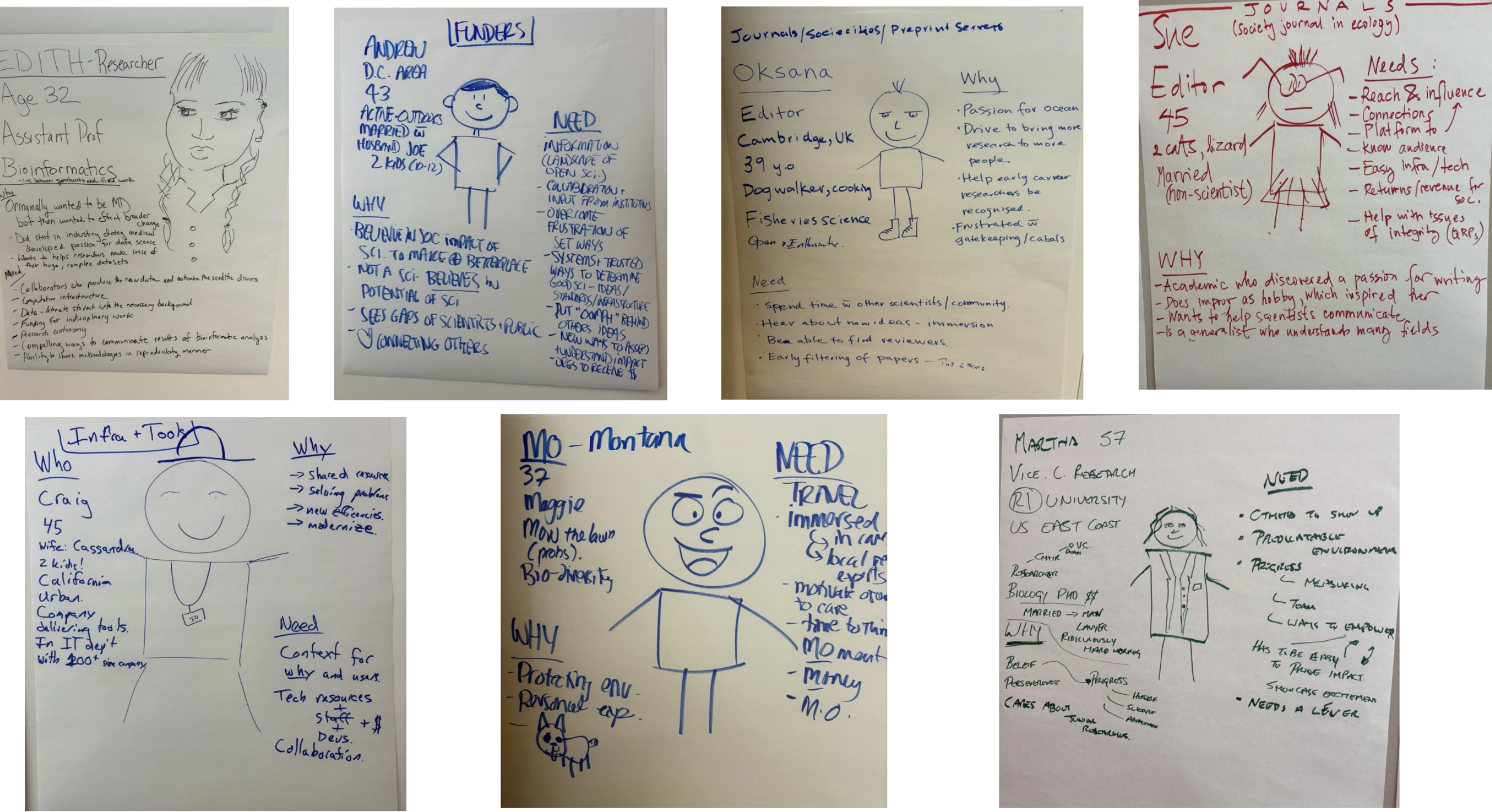

After grounding ourselves in the case studies, we turned our attention to the diverse ecosystem of stakeholders shaping scientific communication. To build a more inclusive, impactful, and resilient system, we needed to understand the needs, challenges, and aspirations of everyone involved. We co-developed six key personas—representing researchers, institutions, infrastructure providers, journals, societies & preprint servers, funders, and the public.

Figure 1:The group created and presented personas back to the group. These have been digitized and added to CSFs Reusable Personas.

Pre-Survey Results¶

The goal of the survey was to surface how participants think, feel, and experience scientific communication today and their hopes for its future. The results informed the sessions we designed allowing us to lean into nurturing alignment that already exists, edge into the frictions, biases, or mental models that often hold discussion back.

The overall vibe of the survey was partly sunny with a chance of “well actually...”. There were many bright spots but definitely some cloud cover hanging around. There’s optimism, but also stretches of frustration and fatigue that dim the brightness.

Scientific communication is shaped by a series of deep-seated tensions—ideas that often appear to be in conflict, yet reveal opportunities for transformation when reconsidered. To design better systems for sharing research, we must challenge the assumptions embedded in traditional practices and ask what it would mean to communicate science in ways that reflect how it is actually done. There were four thematic tensions that were present in the survey responses.

- Rigor vs. Speed¶

- There is a prevailing belief that rigorous science must be slow, deliberate, and methodical—an understandable stance given the stakes of credible knowledge. Yet in a world shaped by rapid developments, public crises, and real-time collaboration, the need for timely sharing is more urgent than ever. We must ask: can speed and rigor coexist? And what systems would allow scientists to share responsibly before everything is finalized?

- Finality vs. Iteration¶

- Scientific publishing still privileges the notion of research as a finished product. Traditional journals, preprints, and PDFs reinforce the idea that findings must be polished and complete before they can be seen. But science is inherently iterative—a process of refinement, feedback, and evolution. What if our communication tools mirrored this reality? What are we really trying to preserve when we demand finality?

- Trust vs. Transparency¶

- Transparency is often treated as a substitute for trust: if we can see how research was done, we can trust its conclusions. But transparency alone is not enough—and in some cases, it can feel invasive or punitive, especially in systems that historically relied on prestige and reputation. True trust must be designed into the processes and structures of science, not merely exposed through them. We must distinguish between transparency that builds trust, and transparency that replaces it.

- Access vs. Reuse¶

- Open access has made enormous strides in removing paywalls and legal barriers to scientific information. But access is not the same as utility. Making science truly reusable requires attention to format, structure, and design. Open access solves who can see the research; reuse solves what someone can do with it. If we want science to be built upon, we must design for function—not just availability.

Reframing the Challenges¶

After the presentation of the pre-meeting survey with the summaries of tensions, we had a group discussion on reframing what often feel like intractable challenges. Participants discussed the complex, often conflicting forces shaping today’s scientific communication system. Despite working with good intentions, many actors—researchers, funders, publishers, institutions—find themselves trapped in a system that reinforces individualism, competition, and outdated norms. The conversation surfaced a shared recognition that incentives—whether shaped by prestige, funding, or career advancement—are misaligned with the collaborative and transparent behaviors we want to see in science.

Early in the discussion, participants acknowledged the presence of what some called “gravity problems”—fundamental forces like capitalism, the tenure system, or entrenched economic models that are difficult or impossible to change directly within the scope of this room. Like gravity, these forces shape everything, but railing against them doesn’t make them go away. Instead of getting stuck trying to “solve” these immutable constraints, the conversation shifted to more actionable ground: how to reframe norms (preprint-ing is now normalized, and is only now being fully incentivized), build new practices, and develop tools and infrastructure that can influence behavior at the community and institutional levels.

Participants emphasized that norms—social behaviors reinforced by shared expectations—are often as powerful as incentives, and often can be more malleable. Shame and prestige were discussed as dual forces that can either uphold harmful traditions or be redirected to accelerate positive change. There was a strong call to move away from shame-driven open science advocacy and toward rewarding, inspiring norms—ones that make it desirable, not obligatory, to share, collaborate, and reuse.

The group also identified critical pain points where new infrastructure or coordination tools could have outsized impact: the over-reliance on longform journal articles for credit, the invisibility of modular contributions, and the lack of shared language around what counts as meaningful participation. These are areas where small shifts—new publishing formats, attribution systems, or lab-based communication practices—could make local norms visible and scalable.

Finally, a recurring theme was the power of local action: communities with shared values can lead by example, creating new defaults that ripple outward. Change may not come from dismantling everything at once, but from finding opportunities where motivation and capability align—places where new norms can take root, new infrastructure can support them, and new stories about science can begin to spread.

Iceberg¶

As groups mapped both the current and future states of scientific communication, patterns began to emerge. While the surface often focused on slow publication timelines or inaccessible formats, deeper conversations revealed a need to rethink how science is structured, shared, and sustained. Three powerful themes rose to the top: the need for modular, “snackable” science; a stronger emphasis on team-focused cultures and roles; and a shift toward reusability as a core design principle—not just for infrastructure, but for practice and mindset.

The Iceberg Model helps to move beyond surface symptoms to uncover the deeper root causes of complex issues. Instead of reacting to visible problems, it encourages exploring underlying structures or cultural assumptions driving them. It supports more strategic, long-term thinking by revealing how system elements are interconnected. It also fosters shared understanding by offering a common framework to interpret what’s happening beneath the surface.

Lunch¶

Before lunch on the first day, we set context went through participant introductions, created personas to guide the conversations, went through the pre-survey reflection, reframed the challenges and discussed some of the things we didn’t want to talk about, and then created our Icebergs. We pushed people pretty hard.

Figure 2:Participants thinking and working through the challenges reframing.

Over lunch, we asked people to come back and “wake up in the future”.

Opportunities for a Preferable Future¶

After mapping both the current and ideal states of scientific communication through the Iceberg exercise, we turned our attention to bridging the gap between the two. The next step was to imagine how we might actually get there.

This part of the workshop focused on idea generation—spanning the grounded and practical to the imaginative and aspirational. Building on the insights surfaced earlier in the day, participants revisited the areas they had prioritized for change: What structures or mindsets need to be reimagined? What habits or assumptions could we let go of? What new patterns could we intentionally design toward?

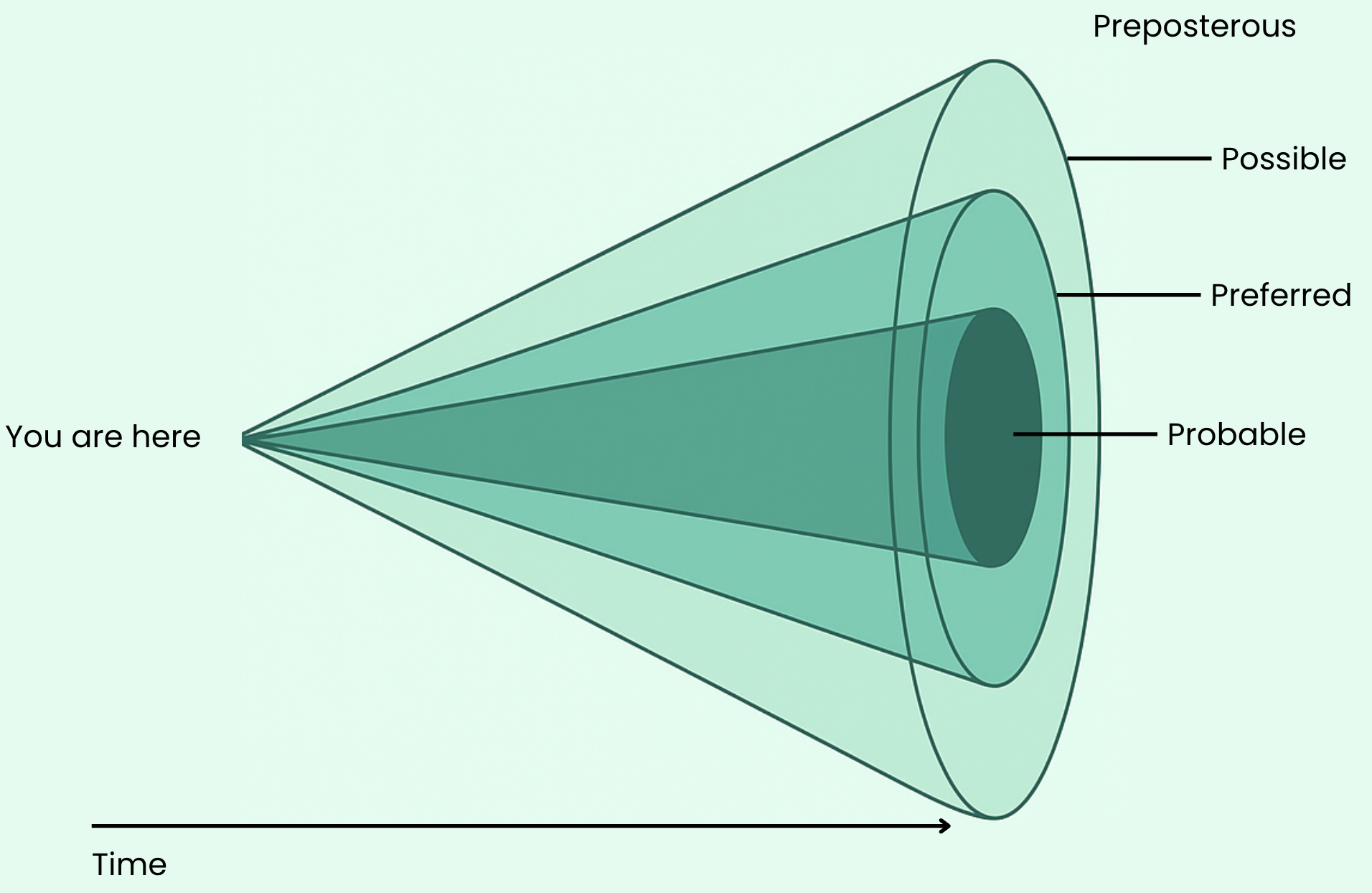

To guide this creative process, we introduced the Cone of Future Possibilities. This exercise is designed by Wildly Open to help organizations think strategically about the future. Rather than focusing solely on what’s most likely to happen, the Cone encourages teams to consider what is possible—and more importantly, what’s worth investing in. It is a tool for pushing beyond current constraints to surface bold, generative ideas that can shape the system, not just react to it.

With the day’s case studies, personas, tensions, and group reflections—and lunch—as fuel, participants began charting new directions—stretching their thinking toward the kinds of futures they not only imagine, but believe are possible to build.

Figure 1:Cone of Future Possibilities. This framework illustrates the range of futures we can imagine—from the probable (what’s likely to happen) to the preferred (what we want to happen), the possible (what could happen), and even the preposterous (what seems implausible today). It encourages moving beyond prediction toward intentional, aspirational design—shaping the future rather than simply reacting to it.

First, each person spent time generating individual ideas—tools, mindsets, cultural shifts—writing one idea per sticky note. In groups of three, they then clustered and refined their thinking, narrowing down to two promising concepts per group. Finally, these trios merged into larger table groups to select three final ideas to pitch back to the room — nine total ideas. These ideas were pitched to the room, then we voted during a coffee break. ☕️ 🗳️

Participants proposed a wide range of ideas to reshape how science is communicated, credited, and reused. These ideas spanned both practical improvements and visionary shifts—grounded in the belief that today’s systems can be restructured to better support openness, iteration, and collaboration. The strongest support went to Composable Science, the idea of breaking research into peer-reviewed components—figures, code, data—that can be reused and cited independently. This was complemented by calls for snackable, modular outputs, project-based websites, and continuous, conversational peer review, all designed to reflect the way science is actually done rather than how it’s currently published.

Other proposals focused on attribution and incentives: authorless papers and contribution graphs would replace traditional author lists with a richer, networked model of credit. New impact metrics would reward engagement, reuse, and diverse contributions—not just citations. Ideas like expanding circles of trust and claim networks introduced new ways to validate and evolve scientific knowledge collaboratively over time. Even though some suggestions—like fully reallocating funding streams—received less traction, the overall message was clear: by investing in modular systems, transparent practices, and infrastructure that reflects how science really works, we can build a more open, resilient, and equitable future.

See the final nine opportunities that were presented to the group and an expansion on Composable Science.

We aligned at a high-level opportunity to focus our energy and movement around: “Composable Science”. We then went to the top of Sulphur Mountain to have dinner, go on a walk — and start to try the movement of composable science on for size.

Figure 3:Dinner was at the top of Sulphur Mountain. We took the Gondola and walked to the summit of the mountain after dinner.

Reflections from Day 1: Clarity, Challenge, and Collective Potential¶

At the end of Day 1, participants shared reflections on the ideas, energy, and challenges that emerged. They were “super impressed by the Jason and Courtney’s facilitation” and “applaud the organizers for such a compelling meeting”.

I learned a lot, and I feel (even more) excited (radicalized?) about open science.

A clear theme was the desire to leave the workshop with concrete actions—not just visionary thinking. “Our goals shouldn’t be timid,” one participant noted, “but they should also be realistic and within our control.” Others emphasized the importance of staying focused on what we can influence, rather than getting stuck on systemic forces and “gravity problems”.

Many appreciated the depth and honesty in the conversations—even when the conversations got uncomfortable, we moved through it as a group. “It was refreshing to go beyond surface-level discussions,” one person shared, “especially when people shared their personal experiences.” There was a strong sense that norms, not just policies, are what need to shift—and that creating local spaces for new behaviors, new forms of credit, and reusable outputs could be a viable way forward.

The idea of composable science surfaced repeatedly as a potential cornerstone for this shift. There was still some heavy skepticism around the concept—especially around use cases, how peer-review might work, and that the concept wasn’t fully articulated. However, many participants described composable science as “concrete and achievable,” with the potential to “enable real-time collaboration, improve attribution, and bring new contributors into research.” One participant captured the mood well:

Composable Science, convergently articulated by multiple people today, has the hallmarks of the beginning of a movement.